News

‹ back to weather news

News

-

Making waves through the Wallace Line

Felix Levesque, 16 November 2024The islands of Bali and Lombok may only be separated by a distance of about 20 kilometres through the Lombok Strait, but an insurmountable depth has kept the Indonesian Archipelago ecologically disjoint for millions of years.

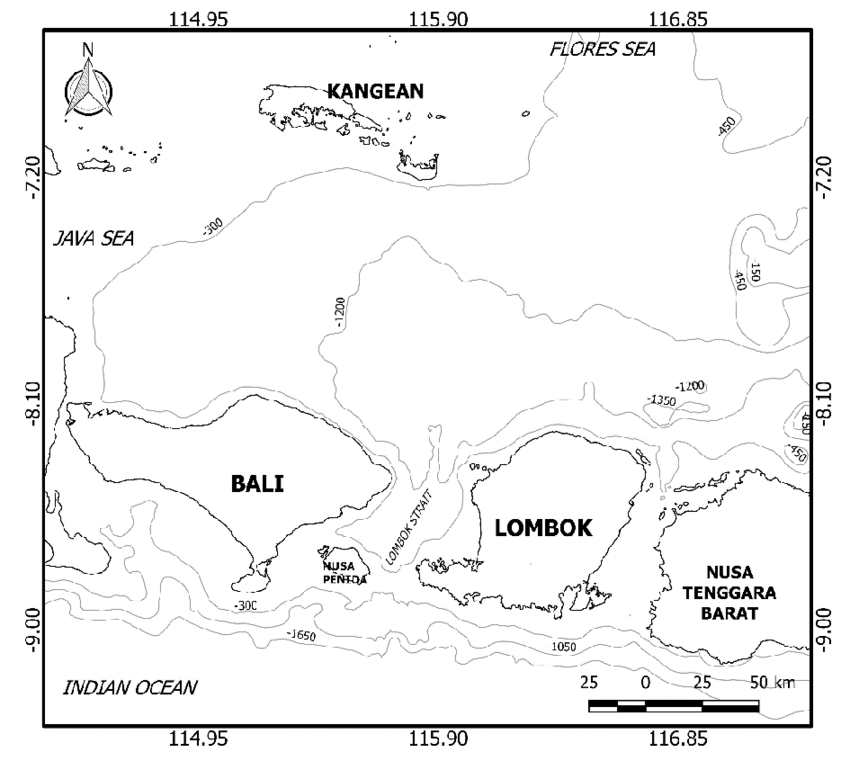

The Lombok Strait is a major component of the greater Indonesian Throughflow, which connects the Pacific and Indian Oceans through massive amounts of water transfers between each ocean. To the north of the strait, in the Java Sea, depths of about 1000 metres can be found, while to the south, in the Indian Ocean, the depth plummets to 3 to 4 kilometres. Deep and wide seas narrows and shallows with the minimum depth of 250 metres across the strait and width of about 20 kilometres, generating a tremendous tightening of the water flow – leading to intense and dangerous currents.

Image 1: The Lombok Strait bathymetry contours (depths displayed in meters). Source: Indonesian Journal of Geography

Local inhabitants of these waters have known for thousands of years about the immense and dangerous currents generated by this flow, with extreme care required in making any strait crossings. The local fauna also reflects this difficult-to-overcome stretch of water. To the east of the strait (so Lombok and beyond to Australia), colourful and exotic birds like cockatoos and parrots and marsupials can be found, more characteristic to Australia’s fauna. On the other side (so Bali and beyond, towards Asia), much fewer brightly coloured birds can be found, replaced by pheasants and fowls happy to live in the jungles that span the Indonesian archipelago. Large terrestrial mammals descendent from Asia like the famous and nearly extinct tigers can (or used to) be found on this side of the strait.

In contrast, flora has been able to overcome the treacherous strait, with plant seeds floating across with no concern for travel time – a feeling similar to those who have experienced the slow and bumpy ferry between Bali and Lombok.

This distinct contrast was first noticed by British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace in 1859 – and was later named after him: the Wallace line. The boundary runs across the Lombok Strait, through the Makassar Strait between Borneo and Sulawesi, and to the east of the Philippine Islands. The division mark the separation between the Sunda Shelf (linking Bali, Borneo, Sumatra and Java) and the Sahul Shelf (linking Australia to islands to the north). During the Pleistocene, shallow seas across the region were easily crossable with sea levels up to 120 metres lower than the current day, allowing free flowing fauna migration within each region. The depth of the Lombok Strait remained prohibitive as it is today, locking species on either side of the Wallace Line.

Image: The probable land masses of Sunda and Sahul when sea levels were up to 120 metres lower than today, with the Wallace Line (along with the Weber and Lydekker lines – other faunal boundaries). Source: Wikipedia Commons

Between the wet season (during the Australian summer) which sees extensive cloud cover and convections, and the dry season (the Australian winter) which sees persistent trade winds, the seas around Indonesia become increasingly smooth. This allows a brief period in between seasons for weather satellites in space to see amazing oceanic processes take hold. Around midday in early November, when the sun is directly overhead, internal ocean waves generated through the Lombok Strait can be seen from space.

Video: Satellite imagery video showing two sets of internal waves propagating north of the Lombok Strait on November 4.

As the tide pushes into the strait, the tightening bottleneck between Lombok and Nusa Penida, along with the powerful current of the Indonesia Throughflow, generate these internal oceanic waves. Zooming out reveals a number of these wave “sets” generated by each high tide, moving at a rate of about 100 kilometres a day.

Video: Satellite imagery video showing several sets of internal waves propagating north of the Lombok Strait, along with fainter waves at the top of the image propagating to the northwest from the Sape Strait between East and West Nusa Tenggara to the east, on November 5.

While these waves will generally pass unnoticed under crossing ships, the effects of the tides pushing in and out of these narrow water passages make for treacherous conditions. Zooming back into the imagery, turbulent waters can be seen following the push of the tide around Bali, Nusa Penida and Lombok. Keen scuba and snorkel visitors who have dived into waters around these parts to see the various reefs and numerous manta rays have experienced the dramatic tidal currents that swirl around these islands.

Video: Satellite imagery video showing a set of internal waves propagating north of the Lombok Strait on November 3 with turbulent waters following the push of the tide.

With the immense tourism load of the main Bali Island, tourists are venturing across the Lombok Strait more frequently, increasing the demand of operators and crowding the powerful waters between the islands. The deep waters also make the Lombok Strait an attractive alternative to the busy Malacca (between Sumatra and Malaysia) and Sunda (between Sumatra and Java) straits, making mariners more enticed to battle the powerful currents – adding to the maritime traffic across these turbulent waters.

- Other news

- Mon 25 Nov 2024 Severe heatwave takes hold of NSW

- Mon 25 Nov 2024 Heaviest rain in almost three years in Victorian city

- Mon 25 Nov 2024 Big stormy end to spring looms for Australia

- Sun 24 Nov 2024 Nature’s air conditioner: how the seabreeze will help Sydney cope during the heatwave

- Sat 23 Nov 2024 Ever Wondered Why It Takes Longer to Fly from Brisbane to Perth Than the Other Way? Here’s the Surprising Reason!